Lysenko and homo sovieticus

March 7, 2011

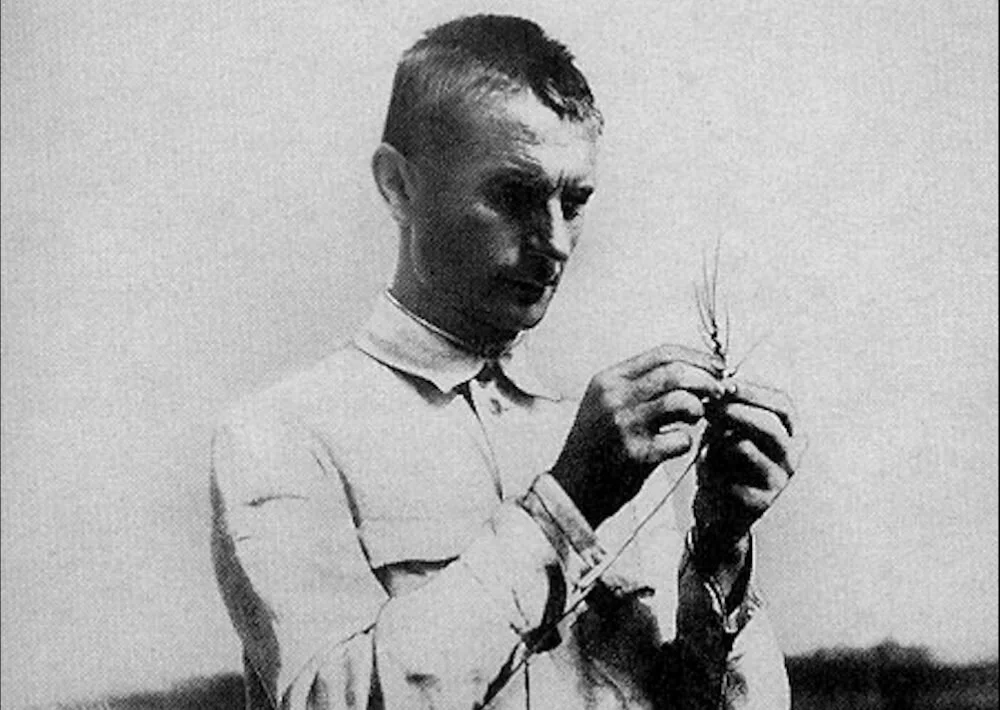

IN A RECENT edition of BBC Radio 4’s In Our Time, the geneticist Steve Jones explained that the failure of the Soviet Union was essentially a failure of Lamarckianism. Or, to put it a different way, a fraudulent and thoroughly despicable Lamarckian called Trofim Lysenko believed that seeds could be “vernalized” – that is, frozen in order to somehow “learn” how to thrive in tough, winter conditions. These lessons could then be passed onto the next generation of seeds.

Lysenko’s anti-Darwinian views won the favour of Stalin, for whom the eternal, unerring processes of ordinary natural selection were heretical. Essentially, Jones explained, Soviet society was in effect an experiment based on the idea that human subjects could inherit acquired characteristics, that a generation could in effect be “vernalized” and turned into Homo sovieticus, after which, generations of citizens would live in uncorrupted, communal bliss.

In fact, they remained more or less the same, with the same failings, the same superstitions, the same general desire to be free to fulfill their own aspirations. Right theory, wrong species, as E.O. Wilson once described Communism.

Perhaps there is something of this sort going on in China right now, with the old guard continuing to silence and crack down on “counter-revolutionaries” on the expectation that these bad seeds will die out, that the desire for freedom of expression is somehow a passing fad inculcated by foreign propaganda during a phase of weakness. The idea is that the Chinese people are not yet ready for democracy, and will only be ready once the subversives have been eliminated. But anyone who understands the dialectic process also understands that subversion is inevitable.

There is a marvellous essay to be written about the way Darwinism annoyed the ideologists of the Soviet Union. Darwinism does appear, at first glance, to favour the status quo. It discredits ideologies that believe in the wholesale rewriting of human nature. It posits only incremental change. It implies we are involved in an eternal conflict for resources, power, acclaim, and (crucially) sexual partners.

But it also thoroughly discredits the idea that we possess an inbuilt “higher purpose”, whether it is God or the strange Hegelian process known as “dialectical materialism”.

The truly radical thing about Darwinism is that it absolves us of the awful responsibility of belonging to some sort of divine plan, but it also leaves us unmoored, free (more or less) to do what we want but nauseated by the feeling of utter futility. Why should this be the case? The lemur doesn’t wake up in the morning and start worrying about the way it has wasted its opportunities to be a great lemur, or about the way life as a lemur is meaningless and absurd.

It makes perfect sense for religious people to reject the theory of natural selection, not merely because it refutes the trivial details of the “revealed truths” of Christianity or Islam, but also because it offers an entirely convincing explanation how a world of such verve and variation and vibrancy can be created without the intervention of a supreme being. It also offers an explanation of history that happens by itself, with no end in mind, and no logically driven transition towards Utopia.