The Madman Theory

September 13 2012

In Presidential Leadership: Illness and Decision Making, Rose McDermott recounts how Richard Nixon would try to explain to his enabler, Henry Kissinger, that his rancid and pitiable personality was actually part of a deliberate strategy. He called it The Madman Theory.

Basically, Nixon proffers the idea that if the North Vietnamese or the Russians or the Chinese all think Nixon is out of his mind, they might be more prepared to make concessions. If Nixon is marooned in a fog of booze and bad memories and on the verge of nuking Moscow, perhaps one ought to back down as quickly as possible.

Nixon had instinctively settled on a theory that Thomas Schelling calls the “rationality of irrationality”. In How the Mind Works, Steven Pinker gives the following example:

Schelling points out that the trick to coming out ahead is ‘a voluntary but irreversible sacrifice of freedom of choice.’ How do you persuade someone that you will not pay more than $16,000 for a car that is really worth $20,000 to you? You can make a public, enforceable $5,000 bet with a third party that you won’t pay more than $16,000. As long as $16,000 gives the dealer a profit, he has no choice but to accept. Persuasion would be futile: it’s against your interests to compromise. By tying your own hands, you improve your bargaining position.

In a negotiation, it is often useful to find some way of removing yourself from the process, to make yourself utterly unreceptive to bargains or compromises of any kind. Try to present your terms as a fait accompli that you are simply incapable of changing. If you are a teenage driver in a game of chicken, for example, removing the steering wheel will take everything out of your hands, quite literally.

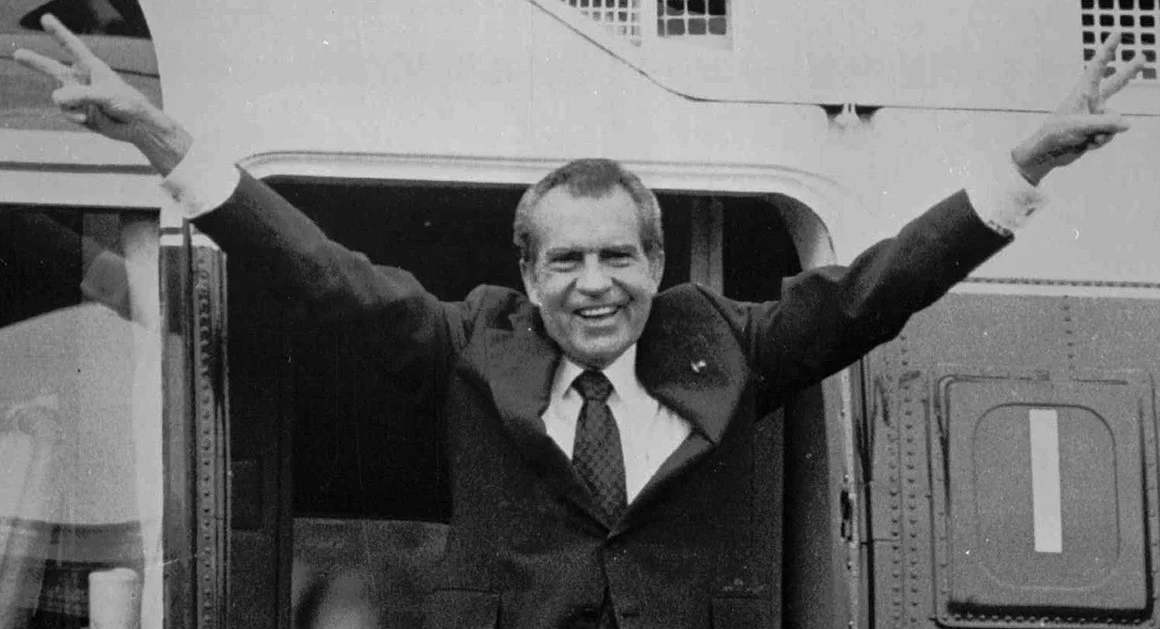

If you are a leader about to negotiate an arms treaty, pretending to be stark-raving mad is as good a strategy as any, I suppose, but in Nixon’s case, something else was going on. Far better to pretend that one is pursuing a deliberate psychological strategy aimed at flummoxing and browbeating one’s opponents than to admit that one is at the mercy of extreme narcissism, paranoia and self-loathing.

One still feels a strange sort of sympathy for him. Nixon’s childhood was truly monstrous -- neglect, violence, squalour, guilt -- and it is shocking that he managed to emerge from it at all, and to emerge as the most powerful man on the planet. It took a truly monstrous ego to fuel his rise to the White House, and the qualities that enabled him to scheme his way to office were the same ones that ensured that he left it in such ignominy. It reminds you of the Douglas Adams aphorism: anyone who actually wants to become a leader should under no circumstances be allowed to do so.

One is struck by the comparison with Gordon Brown, but it is Brown's predecessor, Tony Blair, who has now fashioned himself as a martyr to power, overwhelmed by the enormous responsibilities of the Greater Good, taking on decisions that only a God can bear.