Journey to the West: Ningxia

August 2004

WE ARE supposed to be journalists, but is hard to piece together the impressions one has gathered during nine days of hard travelling that encompassed deserts, famished mountain farms, sleazy provincial cities and several minority communities near the border between Kazakhstan and China. With our schedule packed tightly by the organizers - who happened to be the Shanghai municipal government - and having very little time to settle our thoughts as we fled from one tourist photo-op to another, one day very quickly merged into another. Deserts, after all, are not known for their distinguishing features. Furthermore, a "banquet" hosted by a number of lower-ranked officials in one city might as well have been the "banquet" hosted by a number of lower-ranked officials in another, consisting as it did of the same long embarrassed silences and the dozens of familiar (and inedible) courses - rubber chicken, airplane fruit, old soup - served at the highest speed possible.

The sand and shale and violent heat that lasted for at least a week added to the seamless flow of time, and the hazy, alcoholic amnesia that spread into everything was as attributable to the weather as it was to the copious amounts of baijiu proffered by a variety of tribal hosts throughout the region. Actually, government trips such as these are usually all about the baijiu, a cheap 50%-proof grog fermented from rice. If you are ruined by a few glasses of the stuff, you are hardly in a position to write anything nasty about your surroundings.

One approach in the travel genre is to list everything sequentially. Essentially, one ends up with a slightly more sophisticated version of the old schoolboy Summer holiday mantra of I went to the beach and played ball and then I went home and it was good. Lines are drawn on maps, and one event follows another. When you spent much of the time drunk or in a car travelling across barren landscapes, a map certainly helps, and recalling the precise sequence of the journey already counts as some sort of an achievement.

Alternatively, one can compress everything into themes. In the far western Chinese autonomous regions of Ningxia and Xinjiang, those themes might be portentous and involve the essence of Chineseness, the ambiguity of national borders, the arbitrariness of religious denominations, the notion of progress and of forcing "backward" people to make it, or the convoluted currents of Chinese history itself, which despite the official accounts of a long, unified and uninterrupted culture of five millenia, covers so many swings, rebellions, invasions and countercurrents. Since I have neither an all-encompassing theme (apart from the constant consumption of mutton and baijiu), nor an infallible memory, I can only hope to find the middle ground somewhere.

On that first morning, I was trying to imagine all the possibilities of the trip, including the chance that, somehow, all this was an elaborate trick devised by the authorities to do me down in some way for various unknown moral or political misdemeanours committed in the last twelve months. Only a few days ago, I had read of a team of Taiwanese journalists involved in a car accident in Xinjiang, where the traffic - and more pertinently, the quality of the roads - was reputed to be far worse than in the relatively civilized east. One of them died when a bus hit a sand dune near the city of Hami.

There was also the age-old question of terrorism in the region, a disputed border territory that happens to hold some of China's most promising oil and gas reserves, and is thus treated more stringently than it might otherwise be. Xinjiang, at least, hosts some of the most resentful opponents of Beijing rule, and some of the most fervent were arrested at a military camp in Afghanistan by the United States Army following the overthrow of the Taliban. Just a few days before our trip began, reports emerged of a Uighur "separatist" arrested for making and transporting bombs, and others were expressing their concerns about the Chinese government's overzealous implementation of the "war on terror" in the region. In fact, the Beijing government is continually stressing how peaceful and prosperous Xinjiang is becoming, which is usually a sure sign that the problems persist.

As far as Ningxia is concerned, at least a quarter of the population are members of a Muslim minority, and many of them are living in conditions of appalling poverty, earning far less than the standard poverty-indicator of a dollar a day.

We finally arrived in the early evening, and were met at the airport by various representatives of the local government, including a loquacious English speaker by the name of Chen, the deputy director of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region Foreign Affairs Department.

It needs to be said that every two-bit county or village, every town and city of all descriptions and levels of status, has its own Foreign Affairs Department or waiban. Travelling through southern Jiangsu Province earlier this year, we were greeted by the waiban from countless different cities and counties. As soon as you left one particular jurisdiction, one set of overweight and middle-aged Chinese men with shiny polyester shirts and nylon trousers seemed to melt away, only to be replaced by another virtually identical set. There would be an occasional woman, perhaps the restless wife of some local high-flyer, but most of them seemed interchangeably male and middle-aged, not to mention resolutely on-message.

Ningxia's Mr. Chen did, at least, have the brio and charisma to take charge of the situation. For the first hour or so, the team on the bus on the way to the county of Tongxin, several hundred kilometres away from the regional capital of Yinchuan, revelled in the fluid majesty of his discourse, listening to his descriptions of the misfortunes of Ningxia, the obstacles facing its economic development, the depth of its difficulties, its role in provoking the transcontinental rampage of Genghis Khan during the Western Xia dynasty and the significance of the various landmarks scattered across the length of this, the first of many long car journeys. There was the throttled and parched Yellow River and the patches of yellow land in its bare middle as the region's drought kicked in. There was the gleaming and slightly incongruous pipe infrastructure of an irrigation project, throwing desperate globules of water onto the yellow earth in order to make it fertile for the thousands of peasants currently being relocated from the mountains.

Two hours into the journey, however, Mr. Chen's tireless orations had become, well, tiresome. As he began to talk about Ningxia's position as China's fifth biggest coal producer, or about the setbacks suffered by its reforestation campaign following an infestation of beetles in a fresh copse of poplars, the assembled hacks had begun to twitch and yawn, and had already tuned their minds elsewhere. Outside, smoke from a factory was suspended eerily in the flat blue sky, and our bus soared past dozens of cheaply-built mosques, decked out in gold and green paint. Trucks filled with workers raged violently past our bus, offending the machismo of our driver, who would accelerate.

Yellow was still the main theme. There was the aching Yellow River, winding under the freshly-constructed high-speed roads. There was the yellow earth, stretching almost as far as we could see and urging, begging, gasping for rain.

2.

TONGXIN County is a tiny place, with a population of about 30,000 predominantly Muslim natives. The main road consisted of little more than a series of nondescript apartment blocks and outdoor stalls marked with a line of old and threadbare pool tables. After the banquet with local officials that has already passed into oblivion for all concerned, we wandered out into the town and registered our surprise at the clear, star-pocked skies. Cafes and restaurants were still illuminated by red lanterns, and we began to consider the stories we had heard about local Muslim children rebelling against their parents by frequenting these establishments, drinking the beer they weren't permitted to drink at home. Times were changing, and the government seemed to be encouraging it. In these cynical times, teenage ennui is much more preferable to the sort of Red Guard idealism stoked during the Cultural Revolution, particularly in a desperate region dominated by the symbols and structures of Islam.

We eventually found ourselves in a small cafe called the Sea of Love, where a diminutive youth approached nervously to serve us a few bottles of lukewarm beer. As is common in the Chinese provinces, he would not accept coins. I remembered getting into an argument with a peasant trader in an old town earmarked for demolition along the route to the Three Gorges Dam, after he had refused to accept coins during an attempt to buy a packet of cigarettes. An official later told us that at such a distance from the banks, peasants just don't want to be lugging around too much metal, but the explanation did not seem particularly convincing. It seemed more a question of legitimacy, or a division that had emerged between the cities and the countryside since the reform period, when coins were introduced.

Tongxin County seemed surprisingly prosperous, on the face of it, with locals flying around the streets on Japanese motorbikes and dropping off to drink or play cards with their friends. Someone said that it resembled Shanghai twenty years ago, but it was how my tiny British home town would have been had the police been given instant powers of arrest. This, I eventually persuaded myself, was not a price worth paying. In any case, the poverty, one imagined, was lodged immoveably in the southern mountain villages, which we would visit on the following morning.

On the way from the hotel was the august, forbidding local government buildings, permanently illuminated and built with a sort of Ozymandian grandiosity and sense of omnipotence. The message was, we are here, always, or look on our works and despair.

We ended up at a roadside cafe, only it wasn't much of a cafe. Three or four tables were lined up beside an old stove powered by coal briquettes. Kebabs sizzled on the grill. A grubby boy was sent to buy beer from a slightly better-equipped shop along the road, and we ended up knocking back glasses of the stuff with several of the locals who had gathered to greet us. No one seemed to have much of a conception about the idea of our being reporters, or even our being from abroad. One, who claimed to have already drunk twenty bottles of beer that night, invited us back to his home, or to the nearest karaoke joint, but we declined. He kept looking over at his friend to express surprise about the fact that he could understand what I was saying.

The child - only twelve - turned out to have already left school, was semi-literate and helping his father out with the stall, and with the small plantation they owned and manned during the day. It would be easy to say that what they lacked in education was more than compensated by their warmth and bonhomie. Easy, but patronizing, and typical of the attempts made by foreign correspondents to search for authenticity. Their desperate, empty lives were precisely that, I told myself, and just the same as the ones I left behind in northern England, and should not be romanticized. Still, I consoled myself with the thought that they were, in equal measure, using us as material, and would recall for some time the night when the foreigners came to town.

One journalistic colleague continued to tell everyone how happy she was to see such authentic small-town warmth and joie de vivre. She ought to try living here for a few months, I thought. Moments later, not for the last time, she professed her desire to buy up some cheap real estate in the area and set up a restaurant to meet these pure, good-natured local people.

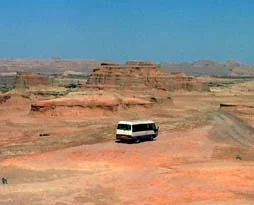

ON THE first morning in Tongxin, we were dragged out of bed at some unearthly hour and driven into the countryside in the impoverished southern mountain region of Ningxia, where the bulk of the Hui Muslims were concentrated. In the harsh, arid loess plateaux some eighty kilometers east of the Yellow River, most of the fields seemed barren. The complex mountain geometry hinted at some higher presence: the unfamiliar brings out the numinous in all of us, but here, there was a strange symmetry in the gulleys that matched the man-made divisions in the cropland down below.

Government slogans about reforestation - "abandon the plough and plant trees", "seal the mountain and prevent grazing" - were inscribed into some of the pale brown hills where neither trees nor grass seemed capable of growing. Little clusters of life would appear on the roadside, with rows of wooden buildings selling illicit petrol or fake ice-cream, and sun-scorched men lugging carts or horses or barrels of water to nearby huts.

Local Hui Minority people squatted in their fields, plucking at the wheat, filthy apart from a pristine white skull cap. Daughters lounged by the roadside, and small donkey convoys edged down the track, possibly on the trail for the water dispensed some 50 kilometres away at the next county, Yuwang.

We were here to see a local celebrity, Ma Yan, made moderately famous by the French journalist, Pierre Haski, who in the course of a visit to the countryside around Tongxin, was disturbed to find that the precocious Ma Yan, then twelve, was unable to attend school largely because of the poverty of her family. After the publication of her diaries in French, a fund was set up with the royalties to help Ma Yan and other impoverished girls in the region attend schools.

Ma Yan is a good-natured fifteen-year old now accustomed to the limelight, unfazed but apparently unchanged by the hordes of visitors, by the hacks and bureaucrats emerging into the loess plateaux to pay their respects. Her home, a newish construction on one of the sharp points of the plateau, was already surrounded by people by the time we had arrived - dozens of tiny unschooled kids flitting and flapping around like pigeons, grizzled old timers gazing on silently, overworked farmers baked dry by the sun. I wandered around the house and looked out onto the fields, the pale parched lines of green and brown on the stepped mountainside, capped by a nude and solitary tree.

We were shown the deep wells, dug into the sandy earth, on which the community depended. They were dry. We were told of the especially harsh spring, about the fifty kilometre round-trips needed to secure the water, and about the disproportionate costs of filling the wells. Local government number-crunchers have worked out that each person earned less than 800 RMB a year, and that was calculated by including the value of crops and livestock. Each barrel of water bought to fill the empty wells was about 80 RMB, a tenth of annual earnings. Small communities coalesce in an attempt to address their common plight, and this added to the desperate claustrophobia of the place. Men with aching, heaving diesel trucks trundle down the mountain to fill their barrels and bring them back. This is a compressed world, driven by the seasons and the harvests.

I asked an old official why they didn't just move the population closer to sea level, and to the rivers. After all, those mad Maoist irrigation schemes of old - where attempts were made to connect every field to some inefficient hand-made contraption pumping water from the lakes - were long gone. The idea that hard work could overcome nature had been soundly trounced once the Maoists had departed and the "reform and opening up" period had got underway in the late 1970s. Sober Dengist realism - "seek truth through facts" - remained the ideology of choice.

And the Chinese government understood, almost to a fault, that the preservation of old communities was never the be-all and end-all. Towns and villages across the country were being destroyed to make way for airports, petrochemical plants, massive hydropower dams or luxury apartment complexes for the nouveaux riche. Surely this desperate, drought-hit mountain world was hardly worth saving, especially if the lives of its people could be made measurably easier by shifting them elsewhere.

"The problem," the old official said, "is that there aren't enough suitable places to move them to. And it's still a bitter life. Some of them even move back to the mountains, because at least they are used to it."

The problem, one would think, has more to do with the fact that there are no huge state-owned companies prepared to buy the land - and pay the derisory relocation costs to local residents. Nothing could possibly interest them here, not even the possibility of a golf course.

In the main room of the house, a massive portrait of Ma Yan and her skull-capped mother filled the whole wall. The whole place had, thanks to Pierre Haski, been set out in homage to the little girl who wanted to go to school. Not for the first time in the course of our journey, the object of our observation had already been transformed, not so much by the fact of our observation - though that was a part of it: the Ma Yan shrine has become one of the legs of journalist junkets in the region - but by a government looking only to show inspiring and sentimental tales of hurdles being overleaped. I made a quiet vow not to write about her at all.

We also heard that much of the money being dispensed for the education of children in the poor farming community of Tongxin County - designated by China's State Council as a "poor region" deserving of state funds - was being squandered by the various local patriarchs, needy of new tractors or of alcohol. It seemed that it wasn't just the government that was corrupt. These were trapped people, ensnared by traditions that were themselves forged over the years by harsh geographic reality. They were unable to lift themselves out of the sands and valleys. They were surely aware - in many cases - of the great modernizing trends in the nearby counties and cities, but they remained somehow isolated from them. Despair, one imagines, would drive many of them into the swelling urban centres to beg or steal or sell themselves. The growth in Islam - at its most fervent, prohibitional, and unforgiving - might be explained as a way of resisting such pressures, and as a way of convincing yourself that the world from which you have been excluded is in any case a product of the devil.

We walked back to our bus, followed along the dust tracks by gangs of local kids and waved away by what seemed to be the entire village, emerging from rows of small one-storey buildings on the hillsides, or from the fields, dropping their scythes for a moment to see what all the fuss was about. We took the bumpy road back to the urban centre of the county, thrown from one side of the bus to another and flung almost to the ceiling by some crevice - some gaping, gasping crack in the surface of the road. The skies continued to burn bright blue, and we took one last look at the smattering of field crops on the stepped slopes of the hills and wondered how long they would survive the encroaching desert.

3.

OUR TEAM of reporters probably all vowed never to take water for granted again. We stared at the fissures in the grey, parched land, looked out in hope at the hapless bursts of colour in the predominantly pale landscape - the sunflowers, the withered grasses, the stooped wheat, the flourishes of purple papaver somniferum - and for the first time in our lives, we prayed for rain.

The rain eventually came, mildly at first, and then viciously, vehemently, but it was probably not enough to fill those wells, and was - in any case - temporary respite at best. Still, by that time, we had already half-forgotten about the plight of the peasants, and were more worried about our survival.

After Ma Yan came a typically overwhelming lunch and then a visit to an old man, a crinkly Hui Muslim establishment figure and former member of the regional Political Consultative Conference, a useless rubber stamp body which most people with real power ignore. True to form, we also ignored the old Muslim, gazed around in embarrassed silence at the artefacts and trinkets and certificates that lined his walls, scoffed some of the fruit he had laid out for us - large piles of locally-grown bananas and melons and grapes - and then moved on to the county's cashmere and pashmina factory, where women in thin cloth masks breathed thin goat-hair fibres into their lungs while plucking strands of wool from a machine for a pitiful 1 RMB (US$ 0.12) an hour. They were, apparently, given only a day of rest every month. Thousands still envied them, with their permanent positions and secure salaries, far in advance of average rural earnings. I watched as a young woman emerged from the cavernous factory building, unwrapped a shawl that had been tied around her throat and mouth, and revealed a curiously beatific smile. She leant on the jamb of the door while I smoked a cigarette. She seemed to watch me, and with all the sentimentality of a relatively prosperous man looking at a dirt poor woman, I imagined she may have been pleading with me to take her away from all this.

There was little ventilation in the building itself, and I felt queasy and clogged up after just three or four minutes in the place. Wisps of hair blew across the breadth of the factory. The women, some of them shockingly young and vital and not yet destroyed by the machines in front of them, gossiped to one another and generally ignored us. Their machines crunched and grinded and eructed, and we moved on. This sort of Victorian sweat shop was now all too common in the rapidly-industrializing Chinese interior, as the coastal enterprises moved further inland to take advantage of the cheap labour. Such has been the regular development pattern throughout the world.

I might have recalled a two-thousand year old legend, in which the purest and prettiest virgin was wrapped in the finest cloth and tossed into the Yellow River in order to placate its God. I might have made some symbolic connection to the sacrifices now being made in the name of something equally spurious.

A large five-hundred year-old mosque (now repaired and reconstructed) then followed. We were then asked to bide our time in a market. Thousands had gathered from miles around to sell their trinkets, their fruit, their shanks of meat, laying everything out under large umbrellas on a crowded market street following the demolition of their building last year. One local Muslim butcher, remarkably (and perhaps unjustifiably) proud of his beard, coaxed me into taking a photograph of him, all the time asking whether I was capable of growing a beard like his. I doubted it.

I was waiting in the shade with a local government official, and he told me that one of the great hopes for the region was tourism. "We get all sorts coming here," the bald little official said. "And all kinds of organizations. The BBC was here. The reporter had grown a long beard and kept telling everyone that he was Bin Laden. The World Bank has been here, looking at their projects. And the International Islamic Development Bank comes here often."

My curiosity was piqued. Wasn't the International Islamic Development Bank indirectly involved in the funding of terrorism? It was certainly motivated by what has come to be known as Wahabbism, designated by most of the tyrannical regions of Central Asia - now known collectively as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization - as the biggest threat to security, and used to justify all kinds of repressive behaviour. The Bank had apparently funded an Arabic School in Tongxin County with more than a million dollars, as well as a girl's school with another half a million, a regional official told me a few days later. Others wondered whether the source of funds was being considered carefully enough in dirt-poor Ningxia.

And so, then came our meeting with Hong Yang, the sheik of the growing community of Ningxia Sufis, now said to be more than a million strong. Smooth, devout and Pakistani-educated, he spoke about his role in the local community, which he insisted was not one of leadership, but of guidance and assistance. He had just returned from one of his duties, settling some kind of dispute between two local families.

As the head of the regional Islamic Association, he was also responsible for selecting those few Hui Muslims allowed to make their pilgrimage to Mecca: 3,000 a year apply, and the number of successful applicants is growing every year, he said, with 600 allowed to leave in 2003. Isolated and remote Ningxia may be, but much of its population identifies itself with a global movement, the icons of which rest thousands of miles away.

There were hints of Hong Yang's own significant personal wealth - a spare but immaculate three-storey house with a set of comfortable bright red sofas, piles of fresh fruit on the table in front of us, the paintings and vases and mod-cons scattered throughout the reception.

He told us that the reason for the growth in Islam in the region was probably the growing prosperity throughout China, and the need for some spiritual counterweight. It seemed more plausible to suggest that it was the desperation, doubled by the growing awareness of other people's prosperity, that fuelled the growth. After all, the disconnected do not start rebellions until they have seen what used to be called the Other. It occurred to me that the worst thing the government could possibly do to the poor was to give them TV sets - windows into the opulence of others. Nomadic hill tribesmen rarely think of their own poverty when they have nothing to compare it to.

He was telling us about the way the government were "redressing the balance" for the vicious attacks on all things religious during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in the 1960s. One example, he said, was the understanding shown by the central government with regard to the One Child Policy.

Mr. Chen of the local waiban told us on the first day that the communities in the southern mountain regions were being encouraged to stick to the one child policy through a programme known as "Fewer Births and More Prosperity". Hong Yang seemed, however, to view the propagation of children as an inalienable right of the Muslim community, even though he conceded that there was a "vicious circle" that linked poverty to more childbirths, and more childbirths to more poverty.

Still, Hong Yang's confidence and relative openness did confirm what a high-ranking regional official had told us privately. Ningxia was probably the most autonomous of all China's "autonomous regions". This was less a result of experimental liberalism than a manifestation of neglect. With their military significance, and the insurrectionary tendencies of their predominantly non-Chinese population, neither Tibet nor Xinjiang have been given a great deal of leeway. Ningxia, on the other hand, just didn't matter enough. Half-hearted state graffiti, spray-painted on rural walls throughout the mountain passes, advised the local population to abjure drugs and protect the environment. Admirable sentiments, no doubt, but one wondered what local peasants made of the occasional, incongruous attempt to promote Jiang Zemin's theory of the "Three Represents".

4.

A GRAND Sunday night followed, on a different street with a different set of people, many of whom were working in a nearby primary school. This, indeed, was the salt of the earth. Our colleague had got it into her head that as a journalist, she would visit what she loftily regarded as the lowest social strata and treat them as if the path to enlightenment somehow resided in them, in the way they subsisted and interacted. Coming from a less exalted social background myself, I was unwilling to view them so romantically. Still, these were good people, I eventually discovered, but I couldn't help feeling uncomfortable, that they were willing to treat us as superstars, deigning to visit their puny little town.

It all began when one of the children of the group sitting in an open-air booth across from us started running from one table to another at high speed, shouting "hello!" in our direction but never staying still long enough to wait for a reply. A married couple, the man half drunk, began calling up their friends to gather by the road side, including a man they had confidently announced to be an English teacher. The man approached, somewhat apprehensively, forced to speak a language he learnt twenty years ago and last spoken six years before, whereupon he had quit the school and taken a position at the local Labour and Social Security Bureau.

A mentally-retarded young Hui Muslim had also attached himself to our pavement party. After being chased away by the owner of the small restaurant that was supplying us with kebabs and beers, he returned, unabashed and curious. We heard later that his father had died only that week, and he was now completely without help.

The stars glimmered. The streets were quiet. Old Hui women selling melons from the backs of trucks waited patiently for custom. Such was our pleasure, we were eventually even persuaded to sing karaoke in the middle of this obscure street miles away from home.

5.

YINCHUAN - the capital of Ningxia - is an expanding city, and forms the basis of the region's urbanization policy. On the first day of our visit to Ningxia, Mr. Chen of the local waiban had told us that Yinchuan was a migrant city - "Genuine locals are very few," he had said - and it certainly showed. One could somehow tell that this was still considered a temporary home for most of the workers here, a place where temporary economic considerations, and temporary lusts, seemed to dominate. The main road - dominated by a Bell Tower resembling the one in the centre of the more renowned ancient capital of Xi'an - consisted of little more than a strip of "talking bars" and bordellos, ill-lit KTV joints and neon-spattered nightclubs.

There was no shame because there was no permanence, and such cities seem to be a fundamental part of the Chinese government's strategy to boost the urban population from the current rate of about 40% to 65% by 2020. They will allow these existing cities to expand, creating suburbs and satellite towns and - the United Nations Development Programme fears - migrant-worker ghettoes stocked full of crooks and hookers from the sticks. Throughout our journey, our attention was quickly drawn to the numbers of girls from the Sichuan farming belt, hanging around the karaoke bars and massage parlours and sending the money they earn back home. They were here in Yinchuan, and they would be in the sweltering city of Turpan in central Xinjiang too.

Even the entrance of our respectable, state-owned hotel was dominated by a large sign advertising the nightly performance of tall and blonde dancing girls from Kyrgystan. I asked Mr. Chen if he had ever been there, and he told us of the restrictions pertaining to government officials in the region. "We're not allowed to go anywhere ñ KTV, nightclubs, red light districts," he said sadly. The same problems did not affect our friends from Shanghai.

Monday was economics day, beginning with the visit to a local vineyard and wine producer. I tried to ask earnest questions of our guide, wondering about the capacity of the wolfberry vats, or the daily output from the bottling machine somewhere further along the production line, but my interest was limited. It was still earlyish in the morning, and we were invited into the wine-tasting room, which was actually a gleaming white laboratory with sinks to spit the wine into, and lights to inspect the colour of the grape. "Being an alcoholic and being a wine connoisseur are two different concepts," I was telling someone while gulping down what seemed to me to resemble cheap supermarket plonk.

After two tedious factory visits in Yinchuan's new economic development zone - I spent one of them, some Japanese machine tool joint-venture, sulking on the steps of the building, waiting for them all to come out - we were granted mercy. After an hour discussing pertinent local issues with three regional officials, we had another mutton- and beer-orientated dinner at a restaurant near our hotel, and then looked for somewhere to drink. We were accompanied by an elder waiban, who seemed to show an unhealthy interest in the city's dark nightspots, the region's cynosures of sex and sleaze concentrated in a single square mile. We wandered into one neon-lit flesh factory, saw a girl lounging on a wooden bench in a backroom and another beckoning passers-by into the front door.

Our early start the next morning, marking the final day we would spend in Ningxia, was for recreational purposes, with the 7.00 bus taking us to some of the region's best-known scenic spots some distance north of the capital. If ancient relics are your thing, then Ningxia has them. Unearthed rocks indicate the seat of government of the Western Xia Dynasty, the last before the great Mongol surge. We were taken to inspect the usual pots and pans and inscriptions, the tattered clothing, the umpteen horse sculptures of the kind seen in the various museums of Xi'an.

We finally got our first taste of rain, a flash shower as we walked towards some stone relic. In the museum lying next to the 1200-year old monuments were various commemorations of Genghis Khan, perhaps the most ruthless and destructive invader in history, but gloriously sinified into a national hero, the founder of the Yuan Dynasty and part of China's continuous five-millenia civilization. Genghis Khan's invasion of China began in Ningxia, which neighbours Mongolia in the north. "It's strange," said one of our Chinese companions, "that someone who invaded China should become a national hero. It's like you British celebrating Hitler."

It is hard to get excited by all this, especially after hours driving in a bus. We came out of the museum and followed a brand-new stone path that led to a series of ancient man-made excrescences dating back from the pre-Mongol Chinese empire, protected from Genghis Khan to some degree by a row of light grey mountains.

And finally, while wandering towards another hulk of hollowed rock that now passes for the remnants of that old world ñ the features, the carvings long abraded by gales of sand - a brief drizzle began to fall. We thought of those wells in the mountains, filling up at least slightly.

In the museum itself, illuminated scale models of the area revealed two large lakes in the middle of Gansu Province, west of Ningxia. The lakes have subsequently been overwhelmed by the encroaching desert, and are simply no more.

Then, finally, came a visit to the curious Desert Lake, an oasis in the middle of the sands, and home to a relatively sophisticated island resort that passes for beach in this remote, land-locked region. I took a old-style open-top cable car to the large dune in the middle of the island, and then tried out a flimsy blue sled sweeping down the slope on the other side, worried more about my camera than about my physical well-being. I then returned to the top of the dune and moved on to the next little game - where, surrounded by excited kids, I was attached to a rope and harness and flung down a wire at high speed to the sands below. Camels and ostriches marched up the side of the dunes, lugging tourists and mugging for the cameras. Youths hung around with cameras, offering to take photographs of tourists doing death-defying stunts with ropes and sleds.

For the second time that day, the skies then opened, and while my heart tried to rejoice for those parched peasants in the mountains, I was soaked, and troubled by the idea of taking the speedboat back to the shore. In the end, I jumped on the boat with three or four of the Japanese journalists and screamed and shouted as we were buffeted by the waves. I thought about the irony of being killed by a rainstorm after writing so much about the water shortages.