Journey to the West: Xinjiang

August 2005

WHILE A sizeable minority of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region are Muslims, the original Muslim settlers - possibly of Turkish extraction - gradually intermarried with local Chinese over a period of centuries, and were it not for the skull-caps and the sprouts of facial hair, one would be hard-pressed to distinguish them from the Han Chinese themselves. In Ningxia, it seemed safe to say, the native Muslims were far more comfortably Chinese than those in Xinjiang.

Xinjiang is a border province if there ever was one, and it has been the subject of repeated crackdowns against the evils of "separatism", "terrorism" and the "east Turkestan" movement. While the Uyghurs form the sizeable bulk of the non-Chinese population in the region, there are also Russian, Uzbeki, Mongolian, Kazakh and Tartar minorities scattered close to China's westernmost frontiers, many of them itinerant herdsmen caught up in a foreign country largely as a matter of chance. This was a hodge-podge of races cohabiting on arbitrary frontiers set up as a matter of convenience by the rival regional powers.

We would, of course, avoid the "terrorist hotbeds" and eventually head north to Altay, taking in a number of recently resettled herding communities ñ as well as some of the region's flashest, swankiest tourist resorts - on the way. Our journey would include the vast Gurbantunggut Desert, the oil-soaked Karamay Mountain, the barren City of Ghosts, the lively Kazakh county of Burqin, and the drearily scenic Hanas Lake, where buses of workers on company day-trips took turns to have their photograph taken in front of landmarks such as the "Sleeping Dragon Bay" and a couple of PLA Helicopters carrying tourists across the mountains, and where the landscape reminded some of central Europe.

It was to involve hours of driving across barren desert plains in temperatures approaching 50 degrees, hours of watching camels heave their way through the heat, hours of wondering where the labourers in the fields and deserts actually went once their long shift had ended.

We were reminded of the worst thing about going on trips like these. Being at the mercy of the government, we weren't so worried about the safety of the journey, but we were thinking about the things that we might have been missing. After all, for them, it was all a question of propaganda. Openly, and without hesitation, officials tell us that they hope "we will make good propaganda (xuanchuan) for them". The word, after all, does not quite have the negative connotations it has in English. Still, in Ningxia, after a conference with some of the region's officials came to a close, one of them said, testily, "I'd like to ask you journalists a question. When you get back to your offices, what will you do for us, for Ningxia?" None of us had an answer.

At least the Ningxia officials were more open than most, and while the usual trips to the flourishing local industries - the cashmere sweat-shops, the huge vineyards - were also on our itinerary, they seemed equally anxious to let us know about the problems in the region. Even so, it was all about presenting a picture of helplessness in the face of the elements. The new openness in some sections of the Chinese authorities - the environmental agencies in particular - is generally prefaced with reference to China's natural geological and geographical disadvantages, for which the government cannot be held responsible.

Urumqi was more or less the same as its equivalents further east, with the usual range of domestic and international brands, the fast-food chains, the construction sites and cranes jousting on the cluttered skyline. Of course, token efforts had been made to preserve the local culture, but they fooled no one. The city, which only 50 years ago consisted of just 100,000 native Uyghur Muslims and a rudimentary economy based on local handicrafts, now has a population of 2 million, 80% of which are Han Chinese. Bar strips and massage parlours prevail, as they do in other migrant cities like Yinchuan, and the occasional Muslim restaurant makes the city no different from Shanghai or Beijing, where Uyghur ghettos can be found quite readily.

Our first morning in Urumqi began inauspiciously, first at the Urumqi New Development Zone headquarters, where Han Chinese workers helped to arrange investment projects for Han Chinese companies on the eastern coast, or for foreign enterprises taking advantage of local tax breaks. Urumqi began to look like an oasis of Chineseness in a desert of ethnic despair and poverty. We were taken to visit a Muslim enterprise, where a local Uighur executive called Arkan greeted us in a factory - decked out in traditional Muslim features and colours, all designed by a local architect - that produced traditional Uighur medicines for the national market. The workers were, according to law, a representative sample of the ethnic mix in Xinjiang, he insisted, but could not be seen at the facility today because they had been given the week off as a result of the high mid-forty temperatures.

Our group was sweating in the factory's conference room, wondering if the sudden crack of the lightbulb meant that the power shortages prevailing throughout China were also affecting this place too. It would certainly explain why the workers had been given a break. Without air-conditioning, one imagined that the temperatures on the factory floor would reach something like 50 degrees.

Curiously, last year's token Uighur on the tour of foreign journalists was the head of Xinjiang Hops. He fled from justice later in the year to avoid charges of embezzlement and corruption.

A wind power facility then followed, where ñ once more ñ employees from eastern China took advantage of the tax breaks enjoyed by Urumqi to build products mainly used in eastern China. Several days later, however, on the way to Turpan, we did see some of the fruits of their labour, with one of the nation's biggest wind farms chugging away in the middle of nowhere, and a special viewing platform built on the edge of the road allowing bored motorists and passengers to take photographs of each other in front of a sign saying, "Wind Power Station".

The Xinjiang Museum was an ill-kempt ruin itself, but it did house several two-thousand year-old corpses excavated virtually intact. The more squeamish among our party wondered if our bodies would be found in an equally well-preserved condition in another two millennia or so. One has to think about the criteria that guarantees such a curious form of survival. The guide insisted that these people were not necessary aristocrats or even landowners, that their families had built a plot in the desert and history, geology and climate had ensured their conservation. In several cases, their teeth were in a better state than my own.

For even further evidence that the Han Chinese had taken over the joint, we were bused to what we expected to be a traditional Muslim bazaar in the centre of the city. The dirt roads had been paved over, the old stalls once lined with imported Turkish junk and native cashmere scarves, had now been demolished, and the most visible monument in the new toytown-like square - apart from a spire filled with photographic homages to the liberation of Xinjiang and the glories of the Chinese Communist Party - was the spanking new Urumqi branches of the fast food chain KFC and the French retail giant Carrefour, neither of which would have tolerated the scrambling commercial free-for-all that existed before.

Still, I wasn't prepared to be silly about this. Progress is, indeed, progress, and I was willing to accept that the open-air stalls that had previously dominated the scene were a significant health and security hazard, especially when each one of them was forced to burn briquettes of dirty coal in order to ward off the harsh sub-zero Winters. The shopkeepers were freezing to death, officials said, and now - with piped heat throughout the new buildings - the situation was much better for them at least. Similar arguments were of course being made for the traders in the market at Tongxin County, who were now hustling on the street waiting for their new quarters to finish construction.

I tried the spire, and was showed around by a vivacious Mongolian girl with typically strong, dairy-fed Mongolian teeth. I looked down at the square below through the dirty windows, and marvelled at the photographs of Chinese revolutionary heroes - Deng Xiaoping standing in front of miracle crop yields, Xinjiang army generals posing statesmanlike while the people smiled happily towards them, gleefully content with the new reality. There were also pictures of Mao Zedong's martyred son.

So, was there really anything much to distinguish Urumqi from a number of middle-sized cities scattered down the eastern coast?

2.

WE FOUND that one distinguishing feature was the ethnic Uighur mayor of Urumqi, a charismatic and immaculately tailored young Muslim leader with the name of Shokrat, who greeted us at the city's main government building.

Discussing the fortunes of the city with him, one of us complained that the city was starting to resemble any other in China. Someone else was expressing disappointment that the bazaar had now been replaced by a number of soulless three-storey buildings. It was true ñ this was pretty much like any other city in China.

The mayor was trying to tell us that the changes were all worth it, and repeated the mantras of growth one hears from virtually every official throughout the land. Urumqi is already tuned in to the rest of the country, already connected via the country's third biggest airport to the major metropolises on the eastern coast. It is fundamentally modernized and Sinified, with the added advantage of having access to the markets of central Asia. It is attracting investment from multinational companies. It is diversifying, and concentrating on the development of the high-tech and service industries. "Don't call us 'remote'," he kept insisting. "We are now connected through transportation infrastructure and the information industry."

None of us asked about the really big things. We probably didn't really want to hear about the impressive GDP growth rates, matched virtually throughout the whole country. We wanted to hear about the way the growth is skewed in favour of the local Han Chinese population, which has expanded considerably since 1949, partly because of deliberate relocation policies, partly because of the mass starvations of the late 1950s and early 1960s, and partly because there are more and more opportunities to be found in the city following the launch of the Development of the West Campaign.

We also would liked to have heard about the troubled spots of Xinjiang, not the oasis of growth that is the regional capital. It is easy to concentrate the economic power of a large region into a big city - as it was in the poverty-stricken Ningxia, where the capital Yinchuan seemed reasonably well-off, and home to all the region's sleaze.

In the case of Urumqi, however, resources were largely controlled by what is essentially an occupying people spreading out into a new frontier (the meaning of Xin Jiang). All great powers have sought lebensraum, and have found moral or historical justifications for doing so, but it should not be forgotten that the bulk of the Han population in Xinjiang are actually migrants.

The mayor was unable to accompany us for dinner, held at breakneck pace in a conference building next to the hotel, but the vice-mayor, a stuffy, awkward, middle-aged woman whose very countenance ñ the way she breathed, the tense glances she gave to her mobile phone ñ proved beyond doubt that there was no other place she would rather not be. Busy waitresses rushed in plates of inedible bean curd, or rubber steaks with some kind of processed potato that may once have passed for French fries, hoping to get the occasion out of the way as quickly as possible. We all had the same idea, and as the plates mounted in front of us, one bowl of cold watery soup piled upon another, one plasticized gourd to add to the rest, we were all looking at our watches and hoping to return to our rooms. The mayor's charisma had evidently sucked out all the personality from the lesser officials working around him. The journalists did not have a chance.

3.

IN THE "oil city" of Karamay, the next leg of our journey, the skewed nature of development in the region was made even more apparent. Again, a predominantly Han Chinese population was shipped in to provide the workforce in a city created from nothing following a Politburo edict in 1958, shortly after the Karamay oil field had been discovered. While Karamay is Uighur for "black oil", the government were never likely to leave its development to the locals.

Once again, one set of local officials had peeled away only to be replaced by new ones, one of which climbed onto our bus to give us a guided tour of the city, the oil field, and the mountain where it had all begun, more than forty years ago, when the pressure from within the rock blew open a large crack at the peak, leaving a pool of bubbling crude. This was not the Beverly Hillbillies, and in this sparsely populated region, where visitors are hard-pressed to spot even a single peasant plantation, the government were able to take instant control. No thieves, and no locals digging illicit wells ñ just a vast 3,000-square metre monocline of untapped black energy.

The natural gas from the mountain still bubbled enthusiastically through the pools of oil. "The biggest problem," said the official, "is the birds that come flying down, thinking it's water. They just get stuck." In the 46-degree heat, one could appreciate their mistake.

Oil trucks lined the new roads cutting through the oil-stained shale. Down in the valley stood the main refinery, and hundreds of pumps bobbing up and down into the wells. There was no visible human presence.

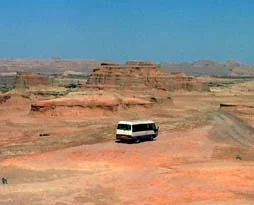

Even ghosts had to have a representative from the waiban. After a few more hours spent winding further through the desert, we finally reached the City of Ghosts, a natural formation of rock close to the Junggar Basin. It got its name from the artifice of its construction, and from the winter winds throwing veils of dust into the air. The city was the ancient product of sandstorms, water and heavy winds, and the heat was sweltering. Melting tires met with melting asphalt.

Meanwhile, our waiban guide - who seemed to have emerged from behind a rock - was pointing out the simulacra of famous faces in the stone, including the pre-revolutionary novelist Lu Xun and, inevitably, Chairman Mao Zedong. Massive hulks of wind-carved sandstone stretched for miles around, some tapering like pyramids. Signs warning of the dangers of landslides had fallen into the sand, unheeded and unseen as we climbed to a promontory. Our guide told us that this was the location of one of the scenes in Ang Lee's celebrated Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon, and that he had personally helped one of its stars, the delectable Zhang Ziyi, down from one of the rocks.

It took several more hours than we had expected to get to Burqin, close to the Kazakhstan border on the Irtysh River. The main road was broken, and apart from a brief interlude of smooth and newly constructed highway, we were forced on a massive detour along dirt tracks. Over the five-hour journey from the City of Ghosts, we crossed miles of semi-desertified land marked by a single electric cable connecting distant rural communities with the national grid. Signs on the road implored farmers not to damage the poles and wires. Others told passers-by to "protect the environment". Looking into the bleak distance, where only the briefest patch of grass broke the sand's monotony, environmental protection already seemed far too late.

It was strange to see the occasional taxi. Where was it going? Was the meter running? It was equally strange to see the people, lounging carelessly by the road side. What were they doing? Where did they live? We effete city dwellers felt as if we had been flung into the far reaches of civilization.

The sands gradually became lush greenland as we moved further north, and blue lakes emerged between the mountains. Eagles swooped across the valley, sheep perched on rocks, and a number of cattle - as cattle does - strayed nonchalantly into the middle of the road.

In Burjin, the paraphernalia of the Chinese Communist Party was more visible than usual. A case of overzealous officialdom working their magic on small-town China, I thought. The local Kazakh official, a taciturn tough guy with a butcher's build, who one imagined had ruled the county with a rod of iron, greeted us with little warmth when we arrived at about one in the morning. We were instantly shipped from our reasonably well-equipped hotel rooms to the home of a resettled Kazakh herding family in a village some 10 km or so away from the main urban centre. We were driven into the gloom of the unlit Chinese countryside, along the tracks and by-ways that now connected these communities with the rest of the world.

Rizabek was the family head, and Zinat was his wife, and the time we spent in his home, squatting in front of a spread of pastries and dried fruits, was not entirely unrewarding. Rizabek, mindful perhaps of the presence of the local officials, proceeded to tell us about the ways his life had improved over the past several years as a result of enlightened resettlement policies. These roaming herding communities in northern and northwestern China had, by now, all been domesticated, brought into the ambit of Chinese society through education and entertainment. Rizabek's fortunes were still determined by animal husbandry, and by the land, and naturally, some other traditions had also been preserved. The milky tea was laced with butter to keep out the winter cold, where temperatures reach about 30 degrees below zero.

Four hours later than scheduled, one of the residents of the village emerged with the ceremonial sheep. No attempts were made to disguise the source of our meal, with its head mounted proudly on a silver platter. After giving thanks to our hosts - our two hands held beseechingly in front of our hearts - we were made to open out our palms as a burly local farmer carved the boiled sheep's head up with a large knife and tore it to shreds. One piece was handed over to each guest, and I had the misfortune of receiving the ear. "Eat, eat, eat," the huge Kazakh farmers continued to repeat, waving their knives at us. I tried to nibble at the gristle, but the man from the waiban's gleeful reminder - "It's the ear! It's the ear!" - put paid to my adventurism.

The ear now secreted in a piece of tissue paper and placed behind me, I was in desperate need of a drink. And I wasn't thinking about the thin yoghurt or the buttery milk tea. "Eat, eat, eat," said a Kazakh farmer, still brandishing his knife and grinning at his guests.

Foolishly, we took their belief in Islam much to heart. It was two in the morning and we were all wondering when, or even whether, we'd be able to get a beer that night. We were also worried that they might take offense, that we'd be in breach of some deeply-held Islamic prohibition. Some of us recalled the glitter and excitement at a market close to our hotel when we first entered the city, where local residents had gathered to eat and drink, and dreamed of being able to return before it closed for the night.

Someone, finally, dared to ask, and beer turned out to be no big deal. And the baijiu also appeared. After several challenges to finish off a single glass in one gulp from Rizabek, I had become strangely numb. Rizabek was now calling us his friends.

They professed a belief in Islam, but it wasn't the pious Islam we saw in Ningxia, nor the militancy we have heard about in western Xinjiang. They seemed to have been caught, by chance, in the expansionary ambit of the religion, eventually paying some kind of homage to a force that had swept into central Asia from Arabia. Their rituals bore a greater resemblance to traditional agricultural land worship, and were certainly closer to the Tibetan Buddhist Mongols than they were to the Hui Muslims. After all, before they were forced to give up their nomadic mode of existence and settle down in homes, they couldn't have given much thought at all to the precepts and callings of faith. They couldn't have seen much of the Koran, or expressed any real need to take the pilgrimage to Mecca. What matters is when the sun rises and when the crops grow. What matters is the harshness of the winter or the ferocity of the summer.

Being a border area, and being at the cross-section of several religious and nationalist expansions, there is a certain eclecticism when it comes to spiritual expression in the region, and some of the old nomads - despite professing their dedication to Islam - would probably hold traditional animist or solar cults more closely to their hearts. Indeed, on one of the plains we stopped off at on the way to the city of Altay, among the yurts and the tiny kids on horseback, were a number of ancient sun-worshipping shrines, abraded almost into nothing by centuries of sand.

The hotel in Burqin was small, with a little counter in the reception staffed by two women - one of which had a speech impediment. I decided to get some more beer, while the Japanese decided to wait for a massage. One of the waiban men was getting lascivious, and the last I heard of him was when he was walking up the stairs to his room, calling down to ensure that the woman who would shortly be dispatched to his quarters was of the requisite age of less than 20 years old. I was drunk, and thought little of it. No one seemed to mind that a representative of the Shanghai government was paying money for barely-legal girls to have sex with him. No one except one of the girls behind the counter, who did not bother to even try to conceal her disgust. I thought about staying to try and demonstrate to her that, well, I was different, but thought better of it.

4.

WE SET off in the morning at about 9, taking a freshly constructed road that wound through the mountains to the resort around the lake Hanas. We had almost crossed the frontier separating China from Kazakhstan. By the time we had arrived at the resort, we were all thoroughly exhausted. This, at least, explained our lack of enthusiasm towards the beauty of the scenery. We were certainly incapable of handling the march up to the top of the mountain that had been proposed by the burly son of the local official.

We couldn't get out of the visit to one of the Mongol families living close to the resort, however. The house owner, Kadesh, a 65 year old who looked much older, told us had been settled in his home for four decades, and had spent most of his life as a herdsman, as had his father and grandfather. He was a Tuwa, one of several nomadic tribes still living outside the ancestral Mongol home.

Cultures are, by and large, porous, and marked by their interactions (usually during conflicts) with others. After years roaming in the plateaux with their herds, the Tuwa family had by now placed a sign on their old house saying "Authentic Tuwa Family", inviting tourists in to watch the master of the household playing an old native flute known as a su'er. On the wall, a portrait of Genghis Khan ñ the Mongolian national hero ñ stood along side a picture of the Panchen Lama in prominently-placed little shrine.

I recalled another tribe, the Ewenke nomadic hunters living in the Inner Mongolian forests, who were resettled last year, the last remaining nomadic tribe to do so. At that time, the same watchwords about progress, civilization, and bringing the community into the embrace of the nation through TV and education, were emphasized. The official media noted that the Ewenke, of Yakut stock and described as "the last living fossils of China", were forcibly removed from their virgin forests and shifted to freshly built houses nearby, mainly in the name of protecting the people and the environment. Such notions of progress were, of course, also considered compulsory for indigenous populations in the United States and Australia.

Our government escorts took us to these areas in order to convince us that the lives of these communities had changed for the better as a result of positive government policies. Age-old questions relating to liberty and choice and civilization arose, and I found myself wondering whether it is right to force communities to change for their own good. Surely it is a good thing that their children now have access to schooling, instead of relying on the mobile vans and horseback teachers as they did in the past. Surely it is a good thing, also, that they have been connected up with the rest of the nation through the power grid, and through television. And yet, there has to be a certain regret at the passing of a pure way of life, I suppose.

Life was tough in the Mongol yurts, and now, transformed by life in their fixed abodes, some of them at least could have a little shelter from the ferocious northern dust winds, and ñ more importantly, it seemed ñ access to national television and a convenient way of educating their children. Previously, the only access their children had to schools was in the form of a roaming, "horseback teacher", approaching their nomadic communities with no fixed schedule.

But there were other sides to the sweeping changes in Xinjiang, not least the reduction of Uighur culture in Urumqi to mere tokenism, and the apparent growth - disputed by the Chinese government - in terrorist activity in recent years. 80 per cent of Urumqi's population was now Han Chinese. Most of the city's wealth, one could not doubt, was in the hands of the Han Chinese.

Whatever is said about the post-Mao era in years to come, it has been a time of unprecedented transformation. Ways of life lasting for millennia have been virtually eliminated. Extreme Maoism ñ often characterized by the conquest and even complete reversal of nature - could not quite uproot the traditions of these communities, but Capital seems more than capable of doing so.

There are other ways that it changes. Taking advantage of the tourism industry, some of these ways of life are being ossified, cast in glass displays, exaggerated and gentrified. The quaint is being conserved for the purposes of the tourists, like butterflies crushed between plates of glass. Our Tuwa Mongol didn't seem to mind, of course. He claimed to be earning 5,000 RMB a year, a third of which was earned through tourism, better than most in the region. Some might think that it's a shame, that things change like this. Erdesh himself seemed rather more pragmatic.

Shortly afterwards, we left Erdesh and his singing daughter to eat in a restaurant down the road. A dozen female schoolteachers from Urumqi had gathered together at the table next to us, and we couldn't resist taking photographs. Some of us ended up drinking too much, and had to march back up the slope to the top of the mountain where our hotel villas ñ now plunged in darkness ñ stood. Marshy and overridden with grasses, I was worried I would never be seen again as I tried to negotiate my way back to my room along a path made of wooden planks. Life could be seen in the near distance, where the fire and light of a party burned.

On the way to Altay, there was yet another meeting with herdsmen in the town of Bosk, where we would have a look at China's reforestation campaign. The Kazakh we met, named Kadesh, was another domesticated nomad, and he was being subsidized to the tune of 160 RMB per mu to plant trees on land that had been damaged by intensive cultivation and grazing. More copious amounts of baijiu then followed, making the next part of our journey - a visit to a hospital specializing in rheumatism and arthritis in the city of Altay - quite impossible. We spent a pleasant hour on the road, our heads poking out of the windows in order to refresh ourselves for the interviews ahead.

And so, at the hospital - a pleasant enough place, as far as hospitals go - I listened with little interest to the introduction given by a nervous doctor in a white coat. There were, he said, 150 members of staff, and after that, your reporter drifted off, shaken out of the stupor only when a fellow journalist nsisted that we go and stare at some of the more stricken patients now held out in the building. Down the corridors, the doors opened to reveal some ancient, bound in off-grey sheets and probably waiting to die. Unhappy with the situation, I stormed out of the building telling everyone who would listen that this was a private matter, and that reporters had no rights to intrude on private grief. Days later, it is necessary to concede that the indignation had its roots in the grog.

5.

WE WERE only given a very brief dinner with the Altay waiban before taking the plane back to Urumqi. We descended into the biggest city around at close to midnight, and after returning to the hotel, the only thing I could do was sleep. Scandals took place during the night, however, forcing our journalist colleague to flee to the reception in her pyjamas to complain about the slamming doors, the high-pitched laughter, and the general whoring and philandering taking place in the room next to her. That room belonged to the man from the waiban.

Most of us dozed until we reached the Bezklik Grottoes, which were said ot date from the Gaochang Kingdom starting in about 460AD. What we learnt here was the racial and religious mixtures that constituted early China, with a variety of feudal plenipotentiaries establishing their throne in the region. Ancient markings indicate the influences of Iranian Manicheism, imported into the Gaochang city in about the ninth century by the Uighurs before they were swept up and converted during the great Islamic expansion. The grottos also suggest that before that conversion took place, the Uighur Khans first converted to Buddhism, and painstakingly restored the Bezklik grottoes. Then, along came Islam. Thousands of Buddhas in another of the grottoes had their eyes gouged out by Muslim Uighurs following a conflict seven centuries ago. It was, I understand, a massive burst of iconoclasm, condemning Buddha to an eternity of blindness.

Many other wall paintings were chipped away by perfidious British, German or Russian explorers in the nineteenth century and, if they were not destroyed in the process, they were then shipped back home. In one case, they were subsequently lost in a fire in Berlin. The German government is, at least, trying to make amends, and is involved in a project with the Chinese to restore some of the crumbling artifacts.

In some of the most intense heat we have ever encountered, we were taken to a number of ancient caves, situated in the appropriately-named Flaming Mountains, where even the camels found it difficult to shake off the lethargy and where tourists routinely fry eggs on the seething stone. This is the scene of legend, where the Monkey King, Sun Wukong, helped guide the monk Xuan Zang past the mountain, noticed that it was in flames. He stole the magic fan of the Iron Fan Princess and put the fire out. Sun Wukong's endeavours did not do much to reduce the heat, with the surface temperatures beneath us hitting 80 degrees centigrade.

In the end, this has always been frontier territory. At another set of sweltering old ruins, the Jiaohe Old City near Turpan, a tiny mountain kingdom was destroyed in a war with the Muslims in the fourteenth century, and the race that lived there were assimilated into the rest of the Chinese community following their defeat. Preserved in the old stone city were roads and temples and a number of dried-out wells.

If we had learnt anything, it was that there is no such thing as a pure society or community. They were never pure. They came in messy waves of migration, absorbed various miscellaneous elements from a number of different cultures, inadvertently changed their nationalities as borders ñ for one reason or another ñ shifted backwards and forwards. And they took advantage of new developments ñ tourism being the most recent one ñ to improve their conditions.

Purists might think it terrible that these traditional communities are now selling <i>kitsch</i> or putting up signs inviting travellers into their house. Purists may think that there is something a little fake about it all, now that the new road has been built through the mountains and connected the areas to the rest of the nation.

Change, change, change. That is what we were being asked to observe in Ningxia and Xinjiang. We soon realized that it wasn't just the rich areas that were being transformed by economic reform. Of course, this being a government trip, we were only being taken to see areas where growth and prosperity had visibly "trickled down" into the lowest orders. The well-fed former nomads now ensconced in large village houses in Burqin County or in the Hanas Mountain Resort told us that they were doing fine. They might have raised cattle for tens of generations, but when new opportunities came around ñ new roads, crowds of tourists ñ they seemed resourceful enough to adjust their living habits accordingly. Whether they were happy about doing so, we never really got the opportunity to found out.

It is easy to get sentimental about it, and wonder why the Mongol, Erdesh, was wearing a grubby cap marked with the words "World Cup" while he played his traditional flute. It is easy to hope for places untouched by what we refer to as civilization, but what we were seeing was something like a zoo, a collection of captive exotica laid out in convenient rows for the tour buses to visit. If they were okay with it, then so were we.

Oh well. What did we expect? That's what all this was about. Tarmac the entire country, fill it with enough industrial parks to create a boom economy, and enough roads to allow the workers to arrive at weekends to look at strangely-garbed tribesmen in their guilded cages. Who are we to say that it is wrong, anyway? Wilfred Thesiger, the great explorer and Jeremiah of Progress, would have deplored any attempts to reduce the diversity of human culture - including its savagery, its blood sacrifices, its brute superstition - to thousands of identical all-amenity fun parks and villa complexes in which the natives put on shows for tourists. But that's the thing with many scions of western culture. Modern plumbing is fine for us, but don't let it despoil all those Asian and African landscapes.